“MANGA.” A form of comic art that originated in Japan, yet has become so widespread that the word is understood globally—a subculture that is arguably no longer “sub” at all. It’s something children lose themselves in, adults get passionate about, and through its expansion into numerous other media, it has become a massive business in Japan. What was your own manga experience like? Maybe you borrowed them from a sibling, stood and read them at the bookstore, passed them around with friends at school, or looked forward to them in a hospital waiting room. Sometimes you’d collect the freebies that came with them and send in reader surveys. Today, it might be Hanashiyomi (reading chapter by chapter online) or posting your thoughts on social media. Every generation has its own magnificent works and its own manga culture. It’s one of the few “common languages” for the people of Japan, a wonderful culture where you can ask, “Did you read yesterday’s chapter?” Here is a whirlwind tour of that manga culture, taking our cues from the “manga magazine.”

The Surprisingly Long History of Manga

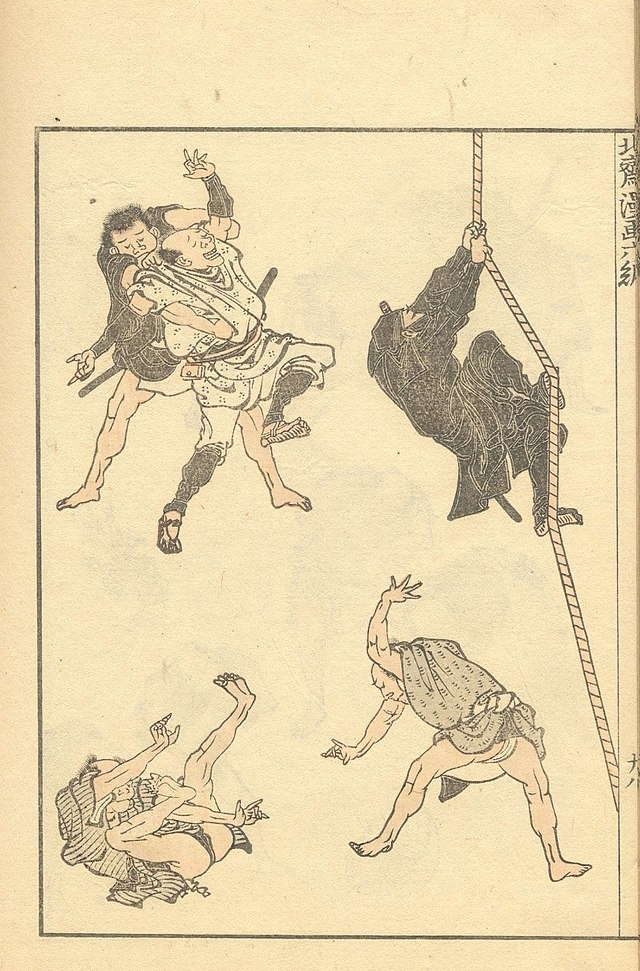

The roots of manga are said to stretch back to the Heian period (794-1185). The origin is often attributed to the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga (鳥獣人物戯画), or the “Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans,” which depict anthropomorphic animals in delightful scenes. By the early 18th century, manga became intertwined with the popular culture of Edo (old Tokyo), leading to the creation of numerous satirical picture books like Katsushika Hokusai’s Hokusai Manga, as well as caricatures and satirical images as a subgenre of ukiyo-e. The uniquely stylized and deformed art style was its starting point of manga.

These charmingly drawn pictures were also popular with children in the Edo period, and picture books for children began to be published. The flourishing publishing culture of the era, as will be depicted in the upcoming Taiga Drama Berabo, also supported this trend. Books like Genpei Seisuiki (Chronicle of the Rise and Fall of the Genpei Clans) and Momotaro Takara no Kura-iri (Momotaro and the Treasure House) had red covers (more accurately, a vermilion color) and were known as akahon (“red books”). This akahon culture would continue, changing its form through the Meiji and Taisho eras, and again after being interrupted by World War II.

The Counterattack of “Children’s Reading Material”

In the pre-war era of manga, masterpieces like Sho-chan no Boken (The Adventures of Little Sho) and Norakuro were born as series in newspapers and magazines. However, during World War II, due to material shortages and information control, manga culture experienced a temporary decline. The one who broke through this was Osamu Tezuka. He sparked a revolution in the world of akahon, which had been considered low-brow reading material for children. His 1947 work Takarajima, New Treasure Island, became a long-running bestseller, and he followed it with masterpieces like Lost World and Metropolis. (It’s a famous story that the excitement of this era is recorded in Fujiko Fujio A’s semi-autobiographical masterpiece, Manga-dō.) In the 1950s, manga created for rental shops, so-called kashihon manga, became widely circulated. Stars like Shigeru Mizuki (GeGeGe no Kitaro) and Sanpei Shirato (The Legend of Kamui) emerged from this scene.

From the late 50s to the 60s, Japan entered its high-growth economic period. Just as the life cycle of busy workers shifted from a monthly to a weekly pace, the world of magazines also shifted from monthly to weekly publications. Catching this wave and applying it to boys’ manga were Shonen Magazine (Kodansha) and Shonen Sunday (Shogakukan), both launched in 1959. Shonen Sunday clearly targeted a younger audience, assembling a team of famous manga artists from the legendary Tokiwa-so apartment building, including Osamu Tezuka, Fujio Akatsuka, Fujiko Fujio, and Shotaro Ishinomori. In contrast, Shonen Magazine became a stage for unique and unconventional talents like Tetsuya Chiba, Takao Saito, Shigeru Mizuki, Kazuo Umezu, George Akiyama, Go Nagai, and Leiji Matsumoto, and would go on to pioneer the gekiga (dramatic pictures) and supokon (sports-guts) genres. The early 60s also saw the launch of weekly shojo (girls’) manga magazines like Shojo Friend and Margaret.

Manga Magazines as Counterculture

In the latter half of the 1960s, during the peak of the Zenkyoto student protest movements, there was a saying: “Journal in the right hand, Magazine in the left.” This referred to the weekly magazine Asahi Journal and Weekly Shonen Magazine. It was an era when manga began to have a major influence on the lifestyles of young people, standing alongside serious political publications. In 1964, Japan’s first youth manga magazine, Monthly Manga Garo, was launched. It was created to serialize Sanpei Shirato’s gekiga epic, The Legend of Kamui. As the weekly magazine style spread, Garo also became a venue for kashihon manga artists who were losing their platforms and a place to discover new talent. As a result, it became a counter-cultural magazine that spread alternative values throughout the manga world. Along with COM, a magazine founded by Osamu Tezuka under Garo‘s influence, it expanded and transformed the very image and concept of “manga.”

Weekly Shonen Jump and the Future of Manga

The 1980s were marked by fierce sales competition among weekly shonen manga magazines. The publication that would come to reign as the king of the manga magazine world from this era onward was Weekly Shonen Jump (launched in 1968), with its editorial policy of “Friendship, Effort, and Victory.” Legendary manga editor Kazuhiko Torishima discovered Akira Toriyama, and numerous hit series emerged, including Dr. Slump, Captain Tsubasa, Kinnikuman, Fist of the North Star, Slam Dunk, and Yu Yu Hakusho. With a strategy that utilized media mix (anime adaptations, etc.), Jump became the undisputed winner, with sales skyrocketing. Its officially announced circulation reached an all-time high of 6.53 million copies for the combined issue 3-4 of 1995 (released in December 1994).

In the 21st century, with the development of technology, the industry faced what is known as the “publishing slump.” Even so, Weekly Shonen Jump continued to produce countless masterpieces, including ONE PIECE, NARUTO, and BLEACH. Today, it has expanded its platform to the app Shonen Jump+. This digital space has delivered works that have become social phenomena, like Kaiju No. 8, Dandadan, SPY x FAMILY, and the much-talked-about one-shot Look Back, showing that the role of “discovery and publication” that magazines once held has now expanded online. Other publishers have also expanded into manga apps, with Shogakukan’s Sunday Webry and Kodansha’s Magazine Pocket. Faced with the publishing slump, manga culture is not ending, but transforming.

The Future of Manga Magazines?

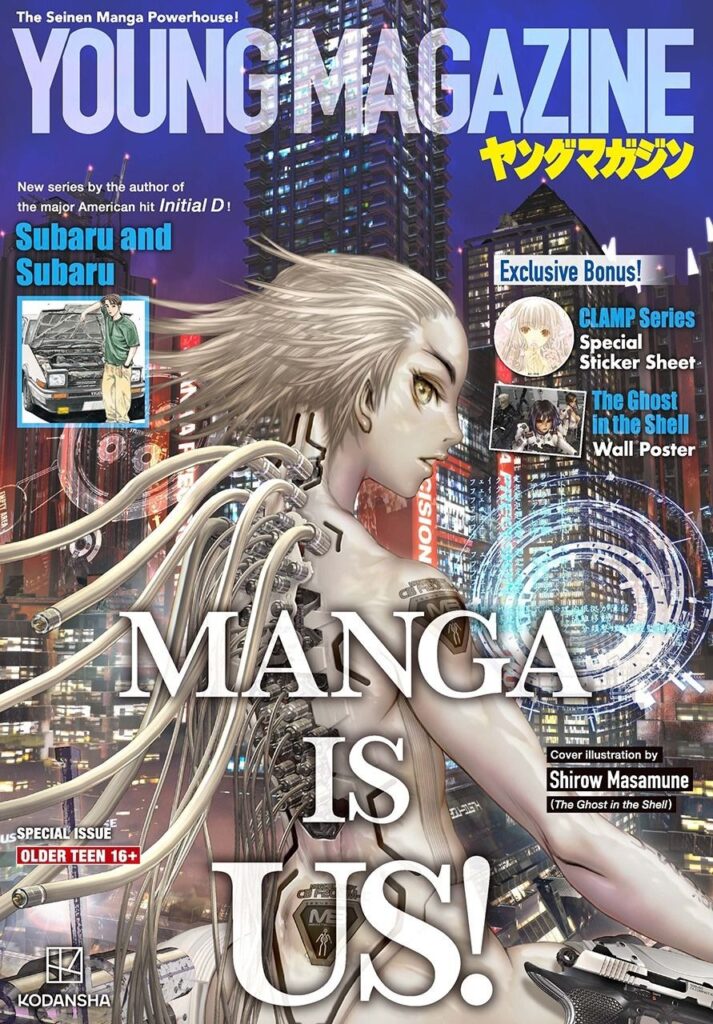

Young Magazine, a youth manga magazine that has produced masterpieces like AKIRA and Ghost in the Shell, published an English-language special issue this summer titled Young Magazine USA. It includes 19 works from a diverse range of genres, including new pieces by Shuichi Shigeno (creator of Initial D) and Shuzo Oshimi (known for Blood on the Tracks). The web version was released on a special site and social media, with plans to conduct popularity rankings via the app and social media as well. It seems to be an experiment in mixing nationalities and media while conveying the core of Japanese manga culture.

In the first place, that “eclectic mix” born from such blending is the very appeal of a magazine, and the “chaotic pages” of manga magazines are what gave birth to manga culture itself. Today, while its form is changing, it is reaching all kinds of people in all kinds of countries and situations. The thrill of opening a page—the wonderful spirit of the manga magazine is now scattered across the world, just like the “Dragon Balls.”